A recurring question I get after discussing the benefits of functional programming (FP) with a developer who is not familiar with FP is, “Ok, that makes sense but how do I actually build a large application out of functions?” In this post I want to look at a simple functional architecture that could serve as a starting point.

I will not be talking about Functional Reactive Programming (FRP) or Functional Relational Programming (also FRP) in this post. These are far more opinionated architectures, trying to achieve specific goals. Instead, I will describe a simple architecture that builds on the core ideas of functional programming covered in a previous post. Let's refresh those here quickly:

- The language it is written in should support higher-order functions

- More complex code should be built from composing simpler functions together

- The programmer should follow the discipline of keeping functions pure as much as possible and push impure functions to the boundaries of the application

Pure functions and higher-order functions will be the main ideas at play here, so if those are not familiar terms, go read this first.

The “architecture” is actually embarrassingly simple. We adopt the pattern of wrapping our features in usecases. This is the name I prefer but I have seen them referred to as feature or even service (I dislike this as it is so overloaded already).

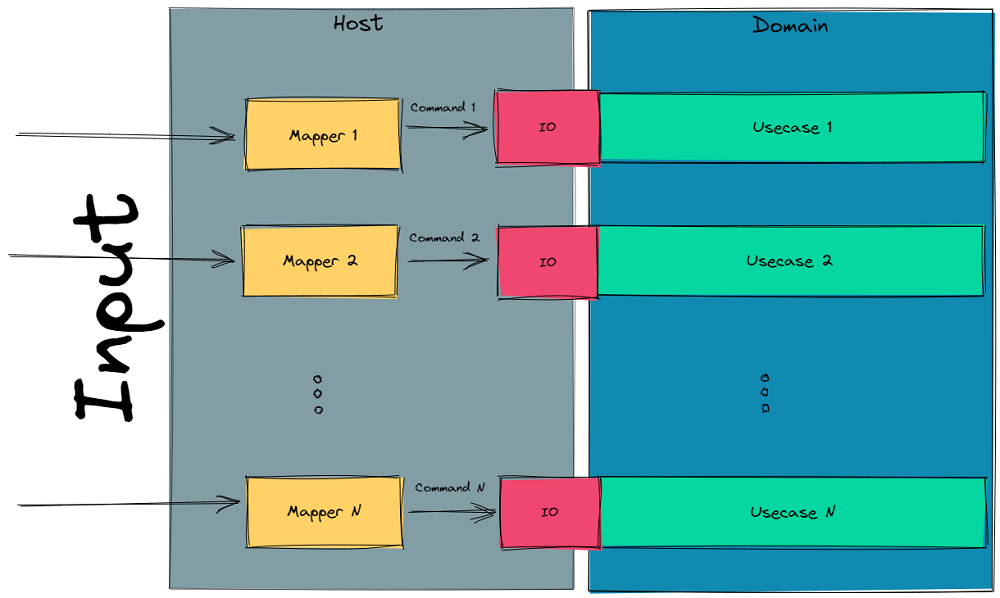

A usecase is called by the host, where the host is typically a web application or a console application (I don't have much experience with desktop or mobile but I don't see why it would differ). The host is also responsible for providing production implementations of impure functions to the usecase.

At this point you might be saying, "Wait, isn't this just Hexagonal/Onion/Clean architecture?". Yes. Maybe it is my background (OOP)? Maybe there are only so many ways to skin a cat? There are more similarities than there are differences.

The important part is the design inside of a usecase. A stark difference between OOP and FP seems to be the separation of behaviour and data. A revelation for me while learning FP was this focus on behaviour. All my professional career I had been modelling data and relationships, and trying to overlay behaviour over this in ways that allowed me to apply business requirements and still felt as if I was working with models of things in the real world. This focus on “things” means when it comes to implementing actual behaviour we end up splitting it between Aggregates, Repositories, Factories, Services, Managers, and ManagerMangers.

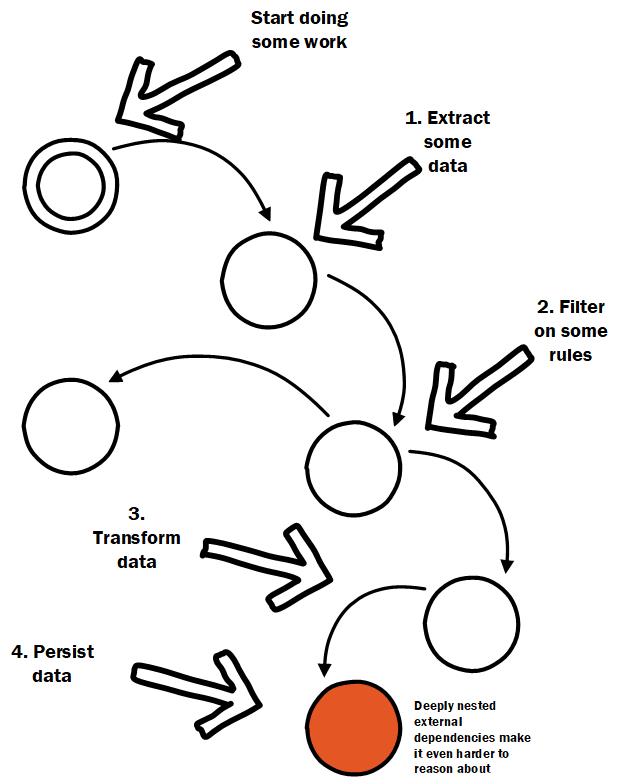

Sprinkling important application logic throughout an object graph makes it difficult to reason about. From post Managing code complexity.

Maybe you have worked on a codebase where dependency injection has run wild and each step is called on an object that was injected into the object executing the current step.

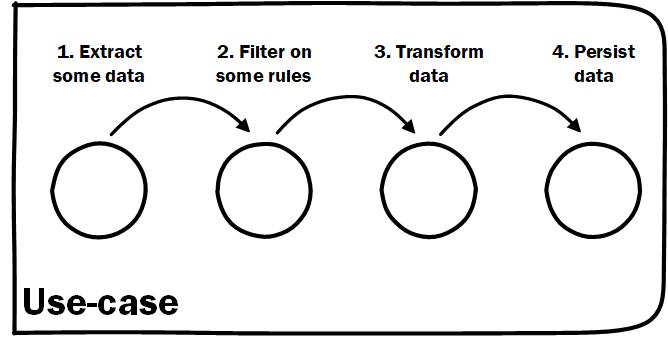

The first improvement for me, that I think was really sparked by more functional thinking, was to make sure I had an entry point that described in clear steps how a usecase is implemented. Functional programming encourages pipelines of behaviour that inspect data, make a decision, and change data based on this. If you think about it, this ETL process is the core of what the programs we write do. Now this isn't yet functional thinking. I wrote about this idea of usecases back in 2018 and whether you are applying FP or not it can improve the maintainability of your codebase.

Usecase as the entrypoint into your domain. From post Managing code complexity.

In using these top level usecases I had gained the benefit of clarity of what happens on a high level, as well as an easy entry point to dive into a specific step. In C# codebases I was using fluent method chaining, making it even feel more functional due to the style. I went through the effort of making my classes immutable.

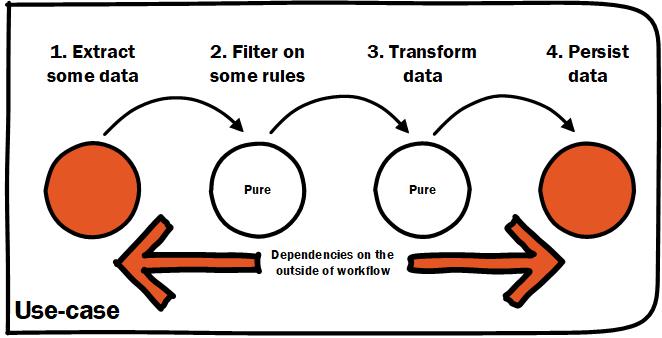

What I did not yet have was the benefits of functional programming. Even though there was a nice clean entry point and a descriptive flow, reasoning and testability where not much improved. Where the functional programming part comes in is in trying to maximize how much of a usecase is pure. The problem was I was mixing chained calls in a “functional style” without making much distinction between method calls that were pure and those that were not.

Impure operations should be pushed to the boundary. From post Managing code complexity.

So what do we get from this approach?

- A high-level list of all usecases in the system.

- An entry point to inspect the steps in each usecase that can be a springboard into specific parts of the codebase.

- Use cases only reference pure logic directly and impure functions can be substituted with test doubles.

An architecture that is easy to understand and easy to test not a bad starting point.

Example code

Let's look at some code snippets of a small example. Unfortunately, architecture only starts becoming important once size and complexity scales up but then examples can become unwieldy. I am keeping things simple here to illustrate the moving parts. Module names like DataAccess and Usecase are a bit on the nose and in bigger applications would not be a good way to organize functionality. I use the names here to make it clear what is inside functions in these modules.

Imagine a little CLI based CRM system. Current functionality is to add a new customer and to change that customers email address. So we expect to have an implementation of a changeEmail usecase.

// implementation of the change email usecase

let changeEmail (readCustomer : ReadCustomer) (saveCustomer : SaveCustomer) (cmd : ChangeEmailCommand) : Result<((DomainEvent list) * Customer),string> =

readCustomer cmd.CustomreId

|> Result.map (Customer.updateEmail cmd.NewEmail)

|> Result.bind saveCustomer

The host provides implementations for the ReadCustomer and SaveCustomer function types. You can see the setup of those below for the CLI tool. Although the details here are not important, something you may notice in the type signature is the events in the return type DomainEvent list. This is a pattern I started using many years ago, even before I started functional programming when I realized raising domain events the moment something happens can cause inconsistencies. If the event is handled and mutates state and then something goes wrong in the main execution path, your events that “happened” don't match your internal state. A safer pattern is to collect domain events as you execute and outbox what you need to at the same time you persist your aggregates.

This usecase is easily testable since the IO parts are passed into the function. You can imagine that as more things need to happen, they can just be appended to the steps in the usecase.

If you are not familiar with F#'s Result type check out Railway oriented programming.

Let's look at how this is used in the console application.

let main args =

// composite root composes IO for app

let readCustomer = DataAccess.readCustomer // real impl would take some config

let saveCustomer = DataAccess.saveCustomer // real impl would take some config

let changeEmail = Usecase.changeEmail readCustomer saveCustomer

let newCustomer = Usecase.newCustomer saveCustomer

// Routing the parsed input

let handle command =

match command with

| Commands.NewCustomer cmd -> newCustomer cmd

| Commands.ChangeEmail cmd -> changeEmail cmd

// Parse the input to a command

let cmd = Mapper.inputToCommand args

// Get result by routing the command to correct usecase

let result = cmd |> Result.bind handle

// handle result output to CLI

With our usecase available, we can parse input to a command that matches to a usecase, in this case the ChangeEmailCommand. This is not an article on F# modelling and frankly it's a bit rough here but the point is that the usecase just received the command and knows nothing of the host.

Tips

- Don't use a usecase in another usecase. Rather have functions that can be shared across different usecases easily.

- If you need to participate or kickoff sagas, an event list is a useful pattern.

- Keep things simple and refactor when things get more complex

- Use specific types as much as possible and build up pipelines inside the usecase that operate on those types

Conclusion

In this post we saw how some core ideas of functional programming like higher-order functions and pure functions come together in guiding us toward an architecture. Mark Seeman has a nice talk about the Pit of Success and Dependency rejection that are worth a watch. We noticed how this relates to patterns we are maybe already familiar with like Clean Architecture and having a core domain that is independent of implementation details. The value add for me is in having an entry-point that describes the steps and for keeping as much of that pure as possible. An alternative would be to really handle the IO outside of the usecase and have the host responsible for composing this together in a meaningful way. In my experience this leaves the usecase as so trivial that it is not worth having. I find it useful to have something that has the domain implementation and pointers to what it depends on to execute it's behaviour.